In October 1874, Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, aged sixteen, left Kraków by train for Marseilles. After three years of sailing from the French port, he joined the British steamer Mavis. From 1878 to January 1894, he voyaged with the British Merchant Marine. From that point onwards, Joseph Conrad pursued a career as an author. In the 1860s/1870s, much of Africa remained a blank canvas to Europeans. Over the next few decades, it was 'opened up' by Europeans - missionaries, 'explorers', traders and armies. It is writ large in History books that this developed into a 'Scramble for Africa'. V. G. Kiernan (The Lords of Humankind, 1969) has written, Africa in this period became very truly a Dark Continent, but its darkness was one the invaders brought with them, the sombre shadow of the white man.

This is the context of Conrad's own journey to the Congo, starting with an interview in Brussels by the Société Anonyme Belge pour le Commerce du Haut-Congo; embarkation from Bordeaux in May; arrival at Boma, the seat of the Belgian Congolese Government in June; further overland trekking to Kinshasa; and then travelling the 1,000 miles to Stanley Falls. Apparently, he did not feel a sense of excitement or achievement; instead a great melancholy descended on him. His boyhood daydreams had been befouled by the actualities of H. M. Stanley and the Congo Free State. This is the context for one of the books he is best remembered for - Heart of Darkness.

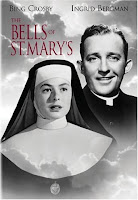

Penguin Books - 1999

(part of a Millennium box set)

I must have bought a Penguin copy of the book back in the 1990s. Having just got through André Gide and Albert Camus (see earlier Blogs), I thought I would continue a Covid-19 Misery Fest, by re-reading the novel. The Penguin printing was diabolical! No margins worth speaking of and small, dark print. Darkness indeed. So, serendipity-like, on a usual pop-in to the Oxfam bookshop in Derby, there awaiting me was a much more reader-friendly edition (see above).

Now, the confession. I had to read the book, short as it is (a mere 110 pages) in three 'bites'. Why? it bored rather than depressed me - heresy! I found the writing 'cold' (a strange word to use, I know). I could summon up little sympathy for any of the characters: Marlow chuntered slowly on, like the big river he was on; Kurtz just became a pain, first in reputation, then in the flesh. More interesting were the African woman, with the helmeted head and tawny cheeks...the barbarous and superb woman, who was the only native not to flinch at the screech of the boat's whistle; and the Intended (of Kurtz), who receives Marlow in her lofty drawing room, coming forward, all in black, with a pale head, floating towards me in the dusk.

By his later years, Conrad was, apparently, set fast in his finicky ways, a stickler for spotless boots, prissy neckties, starched collars, regular mealtimes, and punctilious with ladies and tradespeople. This is how his second son, John, remembered his father (who was 48 when he was born). He got angry with everybody: wife, children, photographers, cricket lovers, eaters of porridge ("damned fish glue"). Oh, dear, he would not be a conducive dinner-companion and would be a long way down my list of Authors I would like to have met! And yet, I must have had my usual spasm of buying a batch of his works and Christine taught The Secret Agent to her students. The ones in my collection are below.

1911 - Penguin reprint 1966 1898 - Penguin reprint 1976

1897 - Penguin reprint 1977 1904 - Penguin reprint 1978

1907 - Penguin reprint 1980 1913 - Penguin reprint 1975

A. N. Wilson (an author I much admire), headed one of his End Columns (3rd September 2001) on The continuing appeal of Conrad's moral universe. He wrote: One of the happiest purchases I ever made was a complete edition of Conrad - £10 for the pristine set...How glad I am to have come to an appreciation of Conrad in advanced middle age! Conrad's great themes, of moral failure, of disappointment not with life but with oneself, are more fully appreciated later in life. Well, not by this 'oldie'. Purblind I probably am; lacking in a certain critical faculty, certainly. But I doubt I will return to Conrad - so many other authors to enjoy, and occasionally endure. I will go back to Camus, possibly even Gide, to top up on my misery quota. I am much more like to watch a repeat of Albert Hitchcock's 1936 film Sabotage rather than Conrad's The Secret Agent. Sorry, Józef .