Wednesday, 29 December 2021

Sheila Kaye-Smith's 'The Tramping Methodist' 1908

Monday, 27 December 2021

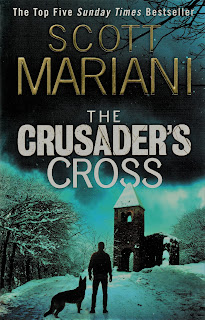

Scott Mariani 24 and Rosie Lear 5

Friday, 24 December 2021

Scott's 'Chronicles of the Canongate' II 1828

Well, I am on the last lap of reading Scott's Waverley novels, having just finished The Fair Maid of Perth. There are just Anne of Geierstein (1829) and the 4th series of Tales of My Landlord (1832) to go. I read the former many years ago, but have yet to sample the delights of Count Robert of Paris and Castle Dangerous. But they are for 2022.

Saturday, 18 December 2021

Scott's 'Chronicles of the Canongate' 1827

The first series of The Chronicles of the Canongate is a collection of three short (of uneven length) stories, which are linked together by a common narrator, Chrystal Croftangry. At least as interesting as the narrator's own story and his Tales is Scott's Introduction, where he not only (finally) confesses his authorship but he explains how his learned and respected friend, Lord Meadowbank, 'unfrocked' him publicly at a public meeting, called on 23rd February 1827 to establish a professional Theatrical Fund in Edinburgh. Scott acknowledged himself to be the sole and unaided author of those Novels of Waverley. The author then went on to thank those who had given him ideas for his novels (Mr Joseph Train for Old Mortality's history; an unknown lady correspondent for the story of 'Jennie Deans'; and a family member for the gist of the Bride of Lammermoor), arguing that he had always studied to generalise the portraits, so that they should still seem, on the whole, the productions of fancy, though possessing some resemblance to real individuals. He also drew attention to the originals of such castles as Wolfs-Hope and Tillietudlem. The scraps of poetry (which I rarely read!) are mainly pure invention.

Friday, 17 December 2021

Thomas Hamilton's 'The Youth and Manhood of Cyril Thornton' 1827

Thursday, 9 December 2021

Galt's 'The Last of the Lairds' 1826

Tuesday, 7 December 2021

Scott's 'Woodstock; or, The Cavalier' 1826

I have, mistakenly, erased nearly all that I had to say about the novel. I cannot retrieve it and I simply cannot face re-doing it. So, for the first time, in this long trail of Blogs, I am simply going to say I enjoyed Woodstock - I approved of Scott's obvious partiality to the Cavaliers and the disguised Charles II; and the marked antipathy towards the Roundheads, particularly, the Fifth Monarchists and Independents, and to Cromwell. The latter, increasingly allowed a marked strain of hypocrisy and power-hunger to overtake any more laudable traits.

I have relented slightly, as I found John Buchan's commentary on Woodstock very helpful.

Woodstock was written in a time of anxiety (Due to the famous 'crash' involving Ballantyne and Constable, Scott's liabilities were £104,081 and the estate available for realization as £48,494, meaning he had to give up his Castle Street, Edinburgh residence after 28 years; the ill health of his grandson; and the death of his wife Charlotte in May 1826) yet the book bears no mark of this sad preoccupation...the opening words of the last chapter seem to be a cry wrung from the heart - "Years rush by us like the wind. We see not whence the eddy comes, nor whitherward it is tending, and we seem ourselves to witness their flight without a sense that we are changed; and yet Time is beguiling man of his strength, as the winds rob the woods of their foliage". But for the rest the book is amazingly light-hearted, and the narrative, hammered out with a perplexed mind, is notably compact. Woodstock ranks high among the novels for the architecture of its plot...is almost the best written of the novels...If it is not to be ranked with the greatest, that is only because it rarely touches the deeper springs of life.

If there was one word I would use about the book, it is warm; a strange word, perhaps, but Scott has a warmth for his characters which few of his contemporaries match. I bought this first edition on 13th February 1982, nearly 40 years ago. How time flies!

Monday, 29 November 2021

Robert Trotter's 'Derwentwater' 1825

I am not sure where to begin with this review; I suppose I could do no better than quote the author's first sentence in his Preface: This Tale is partly historical and partly romantic. Well, what should have been a straightforward account of the Jacobite Rising in 1715 and its march through Carlisle to Preston is mangled by some very odd 'romance'. To put it more simply - Robert Trotter has no idea on how to compose a novel. Luckily, his effort lasts for only 103 pages. The rest of the Volume, pages 108-272, is taken up with an Appendix which, again to quote Trotter, is formed from a large mass of materials collected for a work on heraldry, for which I am indebted to Nisbet, Douglas, and others... I am afraid, I merely glanced through the pages, which consisted of a list of names with a paragraph or paragraphs about who they were and their ancestry; these had little, if anything, to do with the preceding work of semi-fiction.

Sunday, 28 November 2021

Grace Kennedy's 'Philip Colville; or, A Covenanter's Story' 1825

Friday, 26 November 2021

Thomas Dick Lauder's 'Lochandhu: A Tale of the Eighteenth Century' 1825

Saturday, 20 November 2021

Grace Kennedy's 'Dunallan; or Know What You Judge' 1825

Tuesday, 16 November 2021

John Wilson's 'The Foresters' 1825

- Michael's young brother, Abel, who commits forgery and felony, forcing Michael and his wife (his father has died) to move from their beloved Dovenest to pay Abel's debts - but, to another lovely homestead Bracken-Braes. Abel returns, much later in the story, laden with guilt, as was the wretched man, yet in our Father's house there are many mansions - all of them happier and blessed than the most untroubled recesses of any earthy household. Abel dies, but all his knowledge of the Bible revived with his restored power of memory - and he was told, that great as had been his sins, he might hope for the salvation Heaven offered to all believers. When Michael and Agnes travel to the English Lake District - to Ellesmere, hard by Windermere (where the author actually had a home), to collect Scotch Martha, Abel's orphan daughter, they find a wholesome child, to join the other paragons of the tale. She, too, finds love - with Hamish Fraser, a Highlander and another virtuous character.

- Lucy, aged six, is snatched by a gipsy woman, but is restored to the family by a neighbour, Jacob Mayne. Jacob's brother, Richard, notwithstanding his considerable wealth, has been stealing from the church's poor plate. However, he repents and leaves his money to Michael who, in turn, enables it to go to the poorer Jacob. The Maynes were not out of the wood yet. Jacob's son, Isaac, pride of the countryside...a boy of surpassing genius, a boy of many thousand, goes to College and the wider world leads him astray. He returns home, ashamed and shameful, to expire young. His last words were "God bless Lucy Forester!"

- Mary Morrison, is Lucy's closest friend, but has to live with a brutal father, Abraham, with whom the world had gone hardly. She succumbs to one of the only two real villains in the book - Mark Thornhill - who subsequently repudiates his lawful marriage to her, ensuring her father's vengeful behaviour. On his deathbed, Thornhill admits the truth. Mary is re-admitted into 'good' society and ends up serving Lucy and her husband at their new home in the Lake District. Moreover, her father becomes a changed man - patient, even mild - and under the power of a pious penitence.

- Emma Cranston's brother, Henry, long detained in a French fortress, returns to the Hirst soon after his sister's own return from Italy. He is an absolute bounder, a deep-dyed rogue...his passions had run riot in early indulgence...he had formed wild, irregular, and disorderly habits...his had seemed to be the very worst kind of selfishness. His kidnapping of Lucy is swiftly foiled and, although protesting repentance, is soon after found cleanly-dispatched in a duel by a man whose sister he had seduced. He polluted the book!

- The darkest cloud appears to be Michael's loss of sight, after a virulent lightning storm. And yet, there is the silver lining even in what appeared to be a tragedy. Chapter XII, which deals with the immediate aftermath is one of the most moving in the whole novel.