This is now my tenth reading of the Bradcote and Catchpoll series by Sarah Hawkswood. I see that the eleventh is due out in hardback in mid May next year. I will be pre-ordering it with my next Scott Mariani and Susanna Gregory (The Thomas Chaloner series) - the three writers I am presently loyal to. Others - Sam Bourne, Raymond Khoury and Chris Kuzneski, I have given up on, whilst Michael Arnold seems to have stopped at No. 6 in his Stryker series and C.J. Sansom's Matthew Shardlake takes several years to reappear.

Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Sarah Hawkswood's 'A Taste for Killing' 2022

This is now my tenth reading of the Bradcote and Catchpoll series by Sarah Hawkswood. I see that the eleventh is due out in hardback in mid May next year. I will be pre-ordering it with my next Scott Mariani and Susanna Gregory (The Thomas Chaloner series) - the three writers I am presently loyal to. Others - Sam Bourne, Raymond Khoury and Chris Kuzneski, I have given up on, whilst Michael Arnold seems to have stopped at No. 6 in his Stryker series and C.J. Sansom's Matthew Shardlake takes several years to reappear.

Tuesday, 29 November 2022

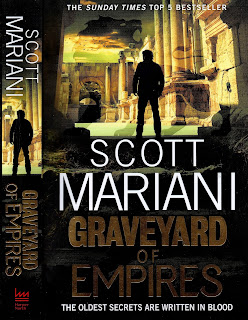

Scott Mariani's 'Graveyard of Empires' 2022

Saturday, 26 November 2022

Mrs Humphry Ward's 'Robert Elsmere' 1888 II

Friday, 25 November 2022

Mrs Humphry Ward's 'Robert Elsmere' I888 I

In The Spectator for 12th November 2022, Roger Lewis had this to say about the recently deceased Hilary Mantel: I'm sorry she died and everything, but I did think Hilary Mantel frightfully overpraised. Her novels will be placed next to Mrs Humphry Ward's - stock impossible to shift in antiquarian bookshops. Whilst I might agree about Mantel and have read only three of Ward's novels, I wonder how many of the latter Lewis has read. Who is Roger Lewis anyway? *

Mary Ward (née Arnold) - who published under her married name of Mrs Humphry Ward - I have written about previously: on 1st July 2022 on her The Case of Richard Meynell, 1911 and on 15th January 2022 on her Helbeck of Bannisdale, 1898. Both single volumes, I thoroughly enjoyed. Robert Elsmere runs to three volumes and is her most well-known book.

Mary Ward dedicated her three-decker novel to two people who had not long since died: Thomas Hill Green, Late Professor of Moral Philosophy in the University of Oxford (d. 26 March 1882); Laura Octavia Mary Lyttelton (d. Easter Eve, 1886). Both are worth concentrating on, so this Blog will be in two parts, the second dealing with the novel itself.

T.H. Green was one of several powerful Oxford ideologues - others were J.R. Green, Benjamin Jowettt and Walter Pater - who cast a spell over the young Mary Ward from the early 1870s. Mary's husband, Humphry, had been coached by Green and the teacher had become his idol; not surprisingly, as he was seen as the most brilliant philosopher in Oxford. Mary and Humphry became good friends with Green and his wife Charlotte. Green's intellectual positions - especially his rational theism - became hers (as can be clearly seen in her subsequent novel). Green distrusted all ecclesiastical and religious structures. He developed a personal Christian humanist stance, conceiving God as the possible self which is gradually attaining reality in the experience of mankind. This was heresy! Green and Mary affirmed God while denying the truth of his revelation - the miraculous Christian story was untenable. Green was one of the thinkers behind the philosophy of social liberalism. Mary was to copy Green in throwing herself into a spiritually therapeutic 'useful life'. The story of Robert Elsmere's journey was to be the same. However, it was in the character of Mr. Grey (a colour link?!) that T.H. Green appeared in the novel.

Mary had first met Laura Lyttelton ( née Tennant) in 1884 at a London party. She became aware of a figure opposite to me, the figure of a young girl who seemed to me one of the most ravishing creatures I had ever seen. She was very small and exquisitely made. Her beautiful head, with its mass of light-brown hair; the small features and delicate neck; the clear, pale skin, the lovely eyes with rather heavy lids, which gave a slight look of melancholy to the face; the grace and fire of every movement when she talked; the dreamy silence into which she sometimes fell, without a trace of awkwardness or shyness. Laura was 22 years-old, one of eight children born to Sir Charles Tennant, the illegitimate son of a Glasgow merchant; her sister was Margot Tennant, later the wife of H.H. Asquith. The Wards were at Laura's wedding when she married Alfred Lyttelton on 21st May 1885 at St. George's Church, Hanover Square. Gladstone gave a speech at the breakfast. Eleven months later, on 24th April 1886, Laura died from complications following the birth of her first child a week earlier. Mary was devastated: I think I was simply in love with her from the first time I ever saw her. Mary was profoundly influenced, not only by Laura, but by the social milieu she moved in. The Cecils, Lytteltons, Tennants and, later, the Asquiths, entranced her. Their power and lifestyle (country parties, balls) linked to the high politics of England was captivating. Laura was to be long mourned by her friends, their closed circle becoming known as the Souls.

I have the biography of Alfred Lyttelton (Longmans, Green and Co., 1917) by Edith Lyttelton. My copy had inserted in the pages a few original letters written by Alfred. One is dated May. 2. 1886 (just a week after Laura's death): My dear Mrs Dawnay, I must tell you of my gratitude for the sympathy you shew me in such tender words. I can hardly face the future but far better men than I have never known any joy in the past. And my memory of the past can never be blotted out...

Mary wrote to Laura's widowed husband, Alfred, asking him for permission to dedicate her novel to her deceased friend. He readily agreed and, after the book was published, he wrote to the author: I must write to offer you my deepest thanks for the perfect dedication, beautiful in its pathos, its tenderness, and just and delicate expression of that which is so hard to convey in words. I read it this morning with blinding tears and yet with truest gratitude... Gladstone stated that Laura remained to the end unshaken in faith. The author told Benjamin Jowett that Catherine Leyburn was meant for Laura - the first section in the novel centres on the psychic strain of a highly-strung girl giving herself in marriage. Mary had seen this dilemma in Laura Lyttelton.

The two dedicatees symbolised the tension throughout Robert Elsmere. More of which in the next Blog.

**************************************************************************

* I have looked up Roger Lewis (b. 1960), who is described as a Welsh academic (are there any?!), biographer and journalist. He has written biographies of Peter Sellers and Charles Hawtrey and is a lover of good art (whatever that means) and bullfighting - the latter casts him out straightaway. He has called the Welsh language an appalling and moribund monkey language and been rude about lesbians (you can always spot a lesbian by her big thrusting chin. Celebrity Eskimo Sandi Toksvig, Ellen DeGeneres, Jodie Foster, Clare Balding, Vita Sackville-West. God love them: there's a touch of Desperate Dan in the jaw-bone area, no doubt the better to go bobbing for apple.) Not worth spending any time on then.

Friday, 18 November 2022

John le Carré's 'Agent Running in the Field' 2019

Thursday, 10 November 2022

T.D. Asch's 'The Century of Calamity' 2021

Wednesday, 9 November 2022

"Went the Day Well?" 1942 DVD