Thursday, 31 August 2023

Two more Jarrolds' 'Jackdaw' novels 1926 and 1925

Two Jarrolds' 'Jackdaw' novels 1931 and 1933

As with the holidays to Greece last Summer and this Spring, I took a batch of Jarrolds' 'Jackdaw' Library paperbacks on holiday - this time to a family villa on the south coast of Spain. I took seven but only managed to read four of them. The weather was too sunny and hot for much of the time (am I complaining?) and relaxing in the pool or simply lying stretched out on a recliner was the most I could do. As for the four books? They were very different from each other, but that's why I like the 'Jackdaw' series. I have now read twelve of the sixteen Crime 'Jackdaws' (I haven't been able to track down the last four yet) and nine of the twenty-two Library series. (I have a further seven on the shelves to read, with only six to find.)

Sunday, 20 August 2023

Two very different novels, both 2022

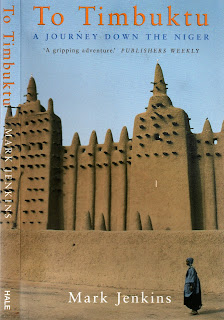

Mark Jenkins' 'To Timbuktu' 1997

Thursday, 10 August 2023

Carlos Ruiz Zafón's 'The Shadow of the Wind' 2001

At the front of the paperback edition are two pages of quotations from reviews from British newspapers and magazines. It is worth quoting some of the comments.

Carlos Ruiz Zafón's wonderfully chock-a-block novel starts with the search for a mysterious author in Barcelona in the aftermath of the Civil War and then packs in as many plots and characters as it does genres - Gothic melodrama, coming-of-age story, historical thriller and more... (Sunday Telegraph).

This gripping novel has the feel of a gothic ghost story, complete with crumbling, ivy-covered mansions, gargoyles and dank prison cells... (Daily Mail)

A complex and absorbing novel...it is a tribute to Ruiz Zafón's skills as a Hollywood scriptwriter that he can create stunning set pieces and bring to life a host of eccentric figures. (The Spectator).

The novel is not an easy read - not because of any problems with the translation by Lucia Graves (daughter of Robert Graves), as it is superb - but due to the fact that it is crammed with intense atmosphere, captivating characters and gripping menace. Furthermore, it is actually a story within a story. In the 1940s, the protagonist Daniel Sempere whose father owns an antiquarian/second-hand bookshop in Barcelona, is taken by his father to the Cemetery of Forgotten books - a secret labyrinthine library that houses rare and banned books. He picks on one entitled The Shadow of the Wind by Julian Carfax and takes it home. Not only does Daniel love the story but he also finds out that the author has disappeared and so have all the other copies of the book and most of his other works. It is not long before other collectors hear about his find, including a mysterious stranger named Lain Coubert (the name of the character of the devil in the book) who has a badly burned and disfigured face.

As the story unfolds more and more characters are drawn into the tale: Don Gustavo Barceló, friend of both Daniel and his father, who offers to buy the book; his daughter Clara, who is blind and 10 years' older than Daniel, who develops a crush on her; the Aguilar family - Tomάs, fiercely protective of his sister Beatriz. who falls in love with Daniel, who returns the love; and, above, all the brilliantly drawn Fermin Romero de Torres. He is quite the most interesting, striking and eccentric person amongst the large cast. Having been tortured by the Falangists of General Franco, he has ended up a beggar on the streets. He becomes a fast friend of Daniel and his father and is used by them to find out many of the secrets (and people still living) relating to Carfax and his books. Their probing into the murky past unleashes the dark forces of the murderous Inspector Francisco Javier Fumero, one-time schoolmate of Julian Carfax.

The book tos and fros between the present and the events of 30 years previously, occasionally making it hard to follow. The detail is far too complicated to explain for a brief Blog such as this. Suffice it to say, the reader gets more and more drawn into its complexities and manages to unpick how the distant past links up with the present sinister twists and turns. I was particularly drawn to the tragic story of Nuria Monfort, who worked at the publishing house where Julian's books were published and who fell deeply in love with him. Sadly, it was not reciprocated as his heart was lost to the ethereal beauty, Penélope Aldaya. Their affair was doomed and it plays a seminal part in the novel's storyline.

The often black/dark humour is part of the charm of the book:

Molins was a cheerful and self-satisfied individual. His mouth was glued to a half-smoked cigar that seemed to grow out of his moustache. It was hard to tell whether he was asleep or awake, because he breathed like most people snore. His hair was greasy and flattened over his forehead, and he had mischievous piggy eyes. I can picture him now!

'People talk too much. Humans aren't descended from moneys. They come from parrots.'

'Blasphemer. You ought to have your soul cleaned out with hydrochloric acid.'

The neighbours have doped her (Pepita) with shots of brandy, and when I saw her, she had collapsed onto the sofa and was snoring like a boar and letting off farts that bored bullet-holes through the upholstery.

Stephen King is correct to label the book a Gothic Novel - it has suspense, dark arts, underground chambers and cells, creepy, ivy-clad mansions, tongue-in-cheek hyperboles, and very strange characters. Rich fare indeed, but not indigestible.

A footnote: It was pleasing to read that the extravagant Catalan financier called Salvador Jausà took as his base the Hotel Colón in Barcelona. So did we, when we had a superb week's holiday in the city.

Thursday, 3 August 2023

Ian Bradley's 'The Call to Seriousness' 1976