Friday, 31 May 2024

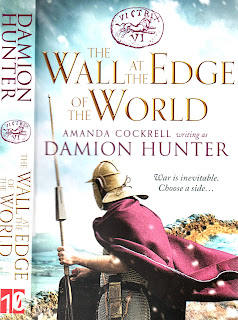

Damion Hunter's 'The Wall at the Edge of the World' 2020

Tuesday, 28 May 2024

Three more Jarrolds 'Jackdaws' 3 'Night Out'

Monday, 27 May 2024

Three more Jarrolds 'Jackdaws' 2 'The Crime at Black Dudley'

Sunday, 26 May 2024

Three more Jarrolds 'Jackdaws' 1 'Madame Holle'

It's another holiday, so I have packed some more Jarrolds 'Jackdaw' paperbacks. The cruise was so chock filled with things to do that I only managed to read three of them.

This was the best of the three. Margery Lawrence (1889-1969) was an English romantic fiction, fantasy fiction, horror fiction and detective fiction author who specialised in ghost stories. There are no ghosts in this tale, even if the building it is set in was probably full of them. In her Foreword, the author says at last (the first edition came out in 1934) she has written a thriller, with the hope that it may supply some small thrill, even devoid as it is of the detective, either amateur or professional, that always seems to be the central figure of any self-respecting thriller! Was that a mild dig at Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, 'Gordon Daviot' et al.?

Minna Clare, cooped up in a frowsy London boarding-house is desperately looking for a job. Her clergyman father had died six months earlier (her mother was long dead) and she has endured three months' fruitless haunting of registry offices, labour exchanges, "bureaux", and the like. A fellow lodger, Gertie Newman, cashier at Briggs' Grocery Stores recalls an ad for a post in Cornwall - as a companion to an elderly lady with delicate son. Minna sends off; she looks to have the job, with a salary of £200, but must send a photograph. Slightly surprised, she does this and gets the position. Thus, with an additional £25 to spend on new clothes (but not anything in blue check), Minna finds herself on a train to the south-west. An extract from the newspaper 'Star', on the dust wrapper of the paperback, states: "Love, mystery, murders - a whole group of them - all play vivid parts in this new sort of thriller". The potential for Love appears on the train - a tall young man stood in the doorway...an eminently pleasant-looking young man in soft heather-coloured tweeds, with a square chin and light brown hair that matched his light-brown eyes...But Minna is having none of it, even though he helps her off with her suit-case. She refuses his offer of a lift and waits for Maude Van der Lyn Holland's chauffeur to take her to Trevarrick. A touch of the Gothick appears at the very gates of the mansion: a high double gate of heavy twisted ironwork set between two square stone pillars mossed with time and crowned with two stone monsters...a rough-looking man in corduroys appears - the gatekeeper - to unlock the gates.

Rather like the opening of du Maurier's Manderlay, the drive is neglected, unlit, close-set each side with a thick bank of laurel and rhododendron behind which loomed heavy dark trees. The house is reached, but there has to be a grinding of locks before it is opened. Once in, the butler shot home once more the huge iron bolts and turned the key. Too late to turn back. Worse was to come - Minna had to meet Mrs Holland, one of the oddest-looking old women she had ever come across! White-faced, black-garbed, gigantic....the huge creature was upon her at once, patting admiring, almost fawning. Later, Minna regards the extraordinary old woman. Over six feet tall, both broad and fat, with large square capable hands and feet to match, she had a face that reminded the startled onlooker of nothing so much as a Christmas mask. A large pallid mask with a series of double chins...The Gorgon, Minna decided was really rather an awful old thing, and stuffed like a pig! If Mrs Holland - regarded as a witch by locals and nicknamed Madame Holle - is odd, then her delicate son is even odder. Both are sinister.

The following morning, an old servant, Tabitha, implores Minna not to stay. Too late. She then meets the son: his eyes were fine, but nearly hidden under black brows drawn into a perpetual frown, and the backs of his hands were thickly covered with a matting of dark hair. Well, that's a worrying feature. One mustn't give away too much of the tale; suffice it to say that the son, Frank Holland, is a thoroughly mixed up and bad, even dangerous, lot. It is increasingly clear that the whereabouts of previous 'companions' before Minna are unknown. We find out why Minna was not to buy blue check and why she had to send a photograph. Into play come secret tunnels, screams from an attic, the reappearance of the 'nice' young man - who proves to be Sir Simon Anquetell, the actual owner of the gloomy house which the Hollands are only renting - red 'flags' flying from a chimney which has to be climbed by Minna; and, finally, an Inspector of Police (not a detective) and Gertie Newman to the rescue. The Hollands are no more; bodies are found; Sir Simon and Minna are to wed; the former may have an old house and a title but no cash; whereas Minna hears she has been left a tidy legacy from her recently deceased aunt, Helen. You couldn't make it up! As the Daily Herald commented: A skilful, splendidly sustained story.

Saturday, 25 May 2024

Scott Mariani's 'The Golden Library' 2024

Tuesday, 14 May 2024

Damion Hunter's 'The Legions of the Mist' 1979

Monday, 6 May 2024

Dora Greenwell McChesney's 'The Confession of Richard Plantagenet' 1913