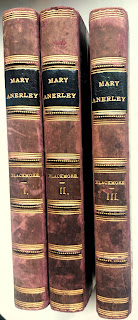

Jarrolds' 'Jackdaw' Library paperback - 1938

It was rather a relief to turn from Ethel Mannin's Crescendo to Margery Allingham's The White Cottage Mystery. Larger text size; more engaging characters; and a narrative which carried you along; all helped. Moreover, it didn't have Albert Campion irritating me on the pages! Instead, Detective Chief Inspector W.T. Challoner of the Yard, incisive but avuncular, after 253 pages manages to clear up the mystery of who shot the nasty Eric Crowther.

The story was serialised in the Daily Express in 1927 and the readers would have waited for the next instalment with bated breath, as it goes at a cracking pace with plenty of twists and turns. Young Jerry Challoner stops his little sporting car in a small Kentish village to offer assistance to a young girl who, just having alighted from a 'bus, was struggling with a heavy basket. He gives her a lift to a pretty little white house set far back from the road, surrounded by a mass of dark shrubbery. They pass by a hideous, grey barrack of a place. The girl clearly dislikes it. Jerry drops her off and meets up with a policeman, red-headed and loquacious. While they are chatting the sound of a shot-gun is heard - it came from the white house.

So begins this spritely tale, where the dead man, the much-despised, hated Eric Crowther, who lived in the neighbouring grey house, could have been killed by any of seven people. Jerry calls his father, who is none other than the Detective Chief Inspector - "Greyhound" Challoner, one of the most brilliant men Scotland Yard had ever known. The suspects? Roger William Christensen, invalid-chair bound; his wife, Eva Grace Christensen, who found the murdered man; her sister, Nora Phyliss Bayliss (the girl Jerry helped home); Estah Phillips, long-time nurse, not only to the five year-old child Joan Alice (who called Crowther Satan), but also to Eva her mother; Kathreen Goody, 17, parlour maid; and Doris James, 40 cook. In addition, there are Crowther's manservant, William Lacy, who is better known to the Chief Inspector as a habitual criminal Clarry Gale; and, finally, an Italian named Latte Cellini, who lived with Crowther, but who has now fled abroad.

There appears to be no shortage of 'evidence', rather a surfeit of it! All the above had a motive for killing the ghastly Crowther. The scene shifts first to Paris and then to Mentone in the South of France as the two Challoners pursue their prime suspect Cellini. Strangely, they encounter Eva and her sister Norah and, then, Lacy/Gale in both places.

A clue to the murderer's identity appears to lie in the fact that - because the gun was found on a table with a scorched tablecloth - the shot that had killed Eric Crowther could only have been fired by a man or woman kneeling...or sitting... It is not until the last few pages, and seven years later, that the reader finds out who the killer was. I only guessed it just before the person was revealed. Clever! I thoroughly enjoyed the fast-paced, twisty storyline. I have now read two of the three Allingham stories in the Jarrolds' 'Jackdaw' Library - The Crime at Black Dudley and The White Cottage Mystery (I preferred the latter) - and just have to track down the third - Look to the Lady - which actually kick-started the paperback series in October 1936.