Wednesday, 27 November 2024

Thornton W. Burgess' 'The Adventures of Reddy Fox' 1913 & Beatrix Potter's 'Mr. Tod' 1912

Tuesday, 26 November 2024

Clarence Hawkes' 'Redcoat. The Phantom Fox' 1929

Sunday, 24 November 2024

Charles G.D. Roberts 'Red Fox' 1905

Friday, 22 November 2024

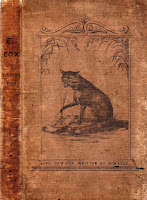

Thomas Smith's 'The Life of a Fox written by Himself ' 1843

Novels on the Fox

I have always had a soft spot for the Fox - ever since I found a deceased one on a teenage ramble through the fields surrounding our home at Holcombe in the wilds of the Mendips, Somerset. I carried it home, slung across my back and deposited it outside the back door of our house, much to the dismay of our Mother. Although I was told to take it back from whence it came, I did chop its tail off before doing so. I kept it for many weeks until the smell forced me to put it in our dustbin. I grew up in the West Indies on tales of Br'er Fox and Br'er Rabbit and always had a sneaking regard for the former. Mr. Tod was also one of my favourite characters in the Beatrix Potter stories. On a trip to London, our family visited the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. I recall being far more interested in the cases containing a badger, a weasel, a stoat and a fox, than the more exotic animals of the world. I still have the four card leaflets I bought then

Then I bought David Stephen's excellent story of String Lug the Fox - published by the Lutterworth Press in 1950. My copy was the Fontana paperback edition of 1957. I still have it, with my childish writing on the fore title: Kenneth Hillier. 1957. Winter Term. Not long ago, I tracked down a copy of the first edition, in its dust wrapper. I now have half a dozen novels relating to foxes, dating from 1843 to 1950. Their front covers appear below. I shall read them all (most again) before Christmas.

Cynthia Harnett's 'The Great House' 1949

Tuesday, 19 November 2024

Cynthia Harnett's 'The Wool-Pack' 1951

Monday, 18 November 2024

Cynthia Harnett's 'The Load of Unicorn' 1959

Friday, 15 November 2024

Cynthia Harnett's 'The Writing on the Hearth' 1971

Sunday, 10 November 2024

Cynthia Harnett's 'Ring Out Bow Bells' 1953

Ethan Bale's ' The Knight's Redemption' 2024

Saturday, 2 November 2024

Another Self - Turkish Series: July 2022 and July 2024

I must admit that I turned to this second Netflix Turkish Series Anotherself (Zeytin Aǧaci) because Tuba Büyüküstün was in it. I had enjoyed her performance - and beauty! - in Black Money Love so much, that it was what they call a no brainer. Ably supported by Seda Bakan as Leyla - a rather scatty, over-exuberant mother of one, with a rafish husband teetering on, and then in, gaol; and Boncuk Yilmaz as Sevgi, suffering from perhaps terminal cancer - Ada (Tuba), is first seen as a successful doctor about to get a prestigious secondment only to botch an important operation on a politician. This was due to tremors in her hand. In fact, she is suspended and later dismissed. The three young women, all in their late thirties, set off for Ayvalik, a small seaside town to recuperate and, even, 'find themselves'.

The main theme, to trace the ancestral roots to problems that each and everyone faces, is developed over the sixteen episodes which make up the two series. The rather sad Ada has to face up to a divorce, an estranged relationship with her mother (who dies early on in the story), the fleeting romances which both lead to break-ups and the loss of her job. Leyla needs to deal with her unsteady, criminal husband and estrangement from her parents. Sevgi, suffering from cancer, has traumas relating to the early death of her father and an ongoing fraught relationship with her mother, who lives with her.

Apparently, the series is an interesting mix of Family Constellation therapy and the use of the book 'It didn't start with You' by Mark Wolynn. Using supporting flashbacks to previous generations, the episodes show how resolving past repetitive family traumas are passed down generation after generation. They encounter the teachings and 'workshops' of Zaman Bey (Firat Taniş) who, ironically it later transpires, has his own estrangement with his son Diyar (Aytaç Şaşmaz).

Towards the end of Series 2, Ada (as a voice over) reflects on what she has learnt - both from Zaman and from reading (Transgenerational Intelligence - repairing the wounds of the past).

- Maybe there's only one reason why we choose to relive the past over and over again. Love. The deep admiration and the subliminal love we feel for the souls who came before us.

- The age-old question we've been trying to answer in 1,001 ways, how do you heal? Perhaps we start to heal when we realize that the past doesn't only give us pain, but that it can also bring us gifts.

- Maybe love actually has a healing effect. When you choose to love and be loved, you start to heal. Or maybe just committing yourself to others can heal you. Even at the cost of hiding your own wounds. Or maybe you start to heal when you accept the responsibilities for the consequences of your choices.

- Maybe some of us get closer to healing when we make peace with our past. And once we start healing our relationships heal with us.

Thus, Ada now sees her dead father as part of her soul. His battered photograph, which she finds in her deceased mother's shabby suitcase, forces her to address both his weaknesses and strengths.

Perhaps, there are too many platitudes from Zaman; Fikret's hair transplant (?) in Series 2 is a bit too obvious; the alternative therapeutic practices, contrasted with traditional methods, may not convince every viewer; Ada is guilty of hypocrisy over her husband's one infidelity when she quickly cavorts with her old love Toprak; but the scenery - both in the olive groves, the beach and the cobbled, narrow lanes of the town is splendid and the acting of a high standard. I found the ending rather contrived. Ada gets a new post, but won't tell anyone where it is. Notwithstanding this, she persuades her two girlfriends, one just reunited with her husband and the other not out of the woods with her cancer, to jump in her car and set off into the sunset. But, of course, a Series 3 is planned for 2025.