Margaret L. Woods

1855-1945

Inevitably these days, my first port of call was Wikipedia. She was the second daughter of the scholar George Granville Bradley, Dean of Westminster and the sister of another writer, Mabel Birchenough. She married Dr. Henry George Woods in 1879. He became President of Trinity College, Oxford and later Master of the Temple. She was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. She is interred with her husband at Holywell Cemetery, Oxford. Apart from collections of verse (published between 1889 and 1921), she wrote six novels and one children's book.

They were A Village Tragedy (1887), Esther Vanhomrigh (1891) - a romance of the loves of Jonathan Swift; Sons of the Sword (1901) - a romance of the Peninsular War; The King's Revoke (1905); The Invader (1907) - a psychological novel; Come unto these Yellow Sands (1915) - about fairies; and A Poet's Youth (1923) - about the early life of William Wordsworth. An eclectic lot! It was the first novel which was referred to and, as usual, that great bookseller, Jarndyce, came up trumps.

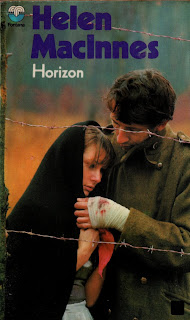

First Edition, 1887

I read the novel over two sessions (it is only 229 pages long) and, thank goodness, in the warm sunshine in the front garden. It is not a book for a darkened room, as it is (almost) uniformly, resolutely grim. The story is of an undernourished fifteen year-old, whose father (her only love) had died, leaving her in a fetid London lodging house with her mother Selina - a bad 'un - who is only too pleased when her late husband's brother James Pontin, takes the girl off her hands, particularly when he grudgingly hands over five pounds. Annie looked very small and childish in the second-hand frock she filled so inadequately... she turns over a small shabby heap of clothes to be placed in a sheet of brown paper on the ground, by way of a travelling trunk and leaves with her uncle: 'Come, come, my girl...don't ye take on so. It's all for the best.' Well - it wasn't!

Her uncle has a farm on the borders of Oxfordshire, in the village of High Cross - a low gabled building some two hundred and odd years old. A Pontin built it, and Pontins have lived in it ever since. On their arrival, the farmer's cart is taken over by Jesse, an overgrown boy, plain and dull of countenance. He is a product of the local Workhouse and is terrified of ever having to return to it. Mrs Pontin, James's second wife, is that used to trouble I don't know what I should do without it. Work, work, work, from morning till night - that's my motto. She loved the human creature in proportion as it approached the animal. Pigs, turkeys, chicken and ducklings were her devoted brood.

Annie is terrified of many of the animals and the only other being that seems to care for her is the ploughboy Jesse. He clung to Annie increasingly as one lonely human creature to another... An important, though minor, character is a 13 year-old idiot boy, Albert, whose unwieldy head rolled loosely on his shoulders, he had a blind eye - a white, viscous-looking eye - and a great shapeless mouth, that was always wet, and generally munching some unclean food. Crises come thick and fast for Annie: her aunt sees her giving a quick kiss to Jesse in the lane. 'You slut! you drab!' she shrieked...You come wi' me, I say, you nasty baggage you little sly hussy!...Them's your dratted mother's ways'... Worse was to follow. Accused of failing to shut up the turkeys, Annie is mercilessly beaten and cast out by her aunt, who says to another villager, Selina - that's Annie's mother - she always was a bad 'un, and black cats mostly has black kits. Annie takes refuge with Jesse. She gets pregnant, thus confirming her aunt's opinion. Although the niece of the old (and useless) vicar's wife gives the couple some help (her aunt seemed to herself and him (the vicar) better fitted to deal with the coarse and commonplace needs of the villagers), the grim tale goes on. Jesse is killed crossing a railway line in the path of an express train, just as he was bringing back a wedding ring for Annie from Oxford. Annie, about to give birth, is hardly helped by her Nurse Mary's opinion that a woman's life was a poor affair for the most part, and that she did not think the little girls of the lower classes would lose much if Judgement Day came before they had taken their turn at it.

Annie tries to commit suicide on the same railway and is only saved through fainting on the embankment; she has her baby - it is a girl, the result she dreaded. Her uncle's response to this knowledge? 'As folks sow, so must they reap.' Denouement comes when she is found in the meadows: there was a look of painful effort stereotyped on the dead face; the square white teeth were clenched, the brows drawn together, and the glazed eyes very wide open, staring up into the clear morning sky. Even her wedding ring, grabbed by the idiot boy, is thrown into the nearby pond.

I tried to find the moral to the novel, and couldn't. Neither Jesse nor Annie had a chance of a happy life; but it was cruel mankind's law rather than nature's. The story is remorseless in its tragic unfolding. Moreover, Margaret Woods's general opinion of the peasantry, the rural labourer, is forthright and rather contemptuous.

The peasant is inarticulate in his loves, like the trees and plants and the many scarcely more conscious things with which he shares (and) the phlegm of the rustic does not, unfortunately, preserve him from an early acquaintance with the grosser vices. Again - the uneducated have a greater appreciation of delicate prettiness than is conventionally supposed.

Why did she write it; what was its purpose? I don't know! A contemporary newspaper review (found in the front of my purchase), argues that she should certainly be ranked among the foremost half-dozen of our living writers...it is regretted that she has not more time to devote to the literary work to which she shows such splendid talent. Both Robert Browning and Lord Rosebery wrote to the publisher, praising the novel. I am sure her other books were much more sunny and optimistic - I certainly hope so.