First Edition - 1945

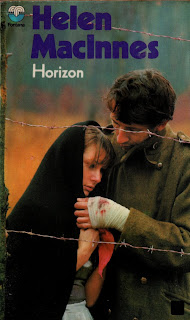

Pan paperback - 1969

Due to its relative brevity, the characters are not as well fleshed out as her three previous books. However, MacInnes's skill in depicting the landscape (her own pre-war holidaying had taken her to Bavaria and further south) produces some powerful passages about the mountain peaks, the darker valleys and gorges, with their rushing streams, and the vineyards and wild flower meadows surrounding the tiny villages. It is also the study of how Lennox's bitterness and dejection slowly changes to a more positive outlook, as he become friends with the Tyrolese and learns to trust Johann, his young guide, in particular. His sense of failure, which exists for much of the book, is relieved by the end as he volunteers to go into North Tyrol to prepare its inhabitants for the projected Allied advance. By the end, Lennox felt he was cured. He could think of the future. A future which included returning to Hinterwald, to repaint the figures on the little church's wall and to meet up again with Katharina Kasal, a young girl who lived in the farm next to his hiding-place at the Schichtl's.

He had stopped brooding about the past: the long, bitter, wasted months and years had lost their power to nag him.

Friends and Lovers, published in 1948, but begun in January 1945 and finished in September 1946, feels like a novel that Helen MacInnes simply had to write. It is the story of an all-embracing love between two young people: David Bosworth, in his last year at Oxford University, and Penelope (Penny) Lorrimer, a would-be artist from Edinburgh. His home is in an unfashionable part of Chiswick, one of eleven boxlike houses...of red brick, now dirty and soot-lined at the seams in a run-down cul de sac, where his resentful younger sister looks after their invalid father; hers in a prosperous area of Edinburgh, with a solid and comfortable three-storied house, with a lawyer father and a mother who is a do-gooding voluntary worker (President of the Rambling for Health Club; Treasurer of the Committee to set up Clubs for Bonnier Bairns; member of a Citizens' League for the Preservation of Ruins). They first meet on the small island of Inchnamurren, where Penny's grandfather has retired to a cottage. MacInnes skilfully details the increasing attraction they have for each other, from the love-at-first sight (he was looking into a pair of very blue eyes in a very pretty face, and that was all he could seems to see...and, a little later on the sea shore...she knew that his eyes were still on her. She felt a strange mixture of excitement and tension and embarrassment, and it wasn't altogether unpleasant), through a contrived 'day-out' in Edinburgh to the growing, almost desperate, need for each other when she moves to London.

MacInnes is equally good at describing the 'landscapes' of the island, the middle-class home in Edinburgh, the dinginess of David's home, the London streets and varied life of 1932-1933, and the Oxford colleges and high-tables of that period. All the characters, even those occupying a brief time in the book are 'alive' and individual - such as Mrs Fane whose white mask which cracked round the lips as they went through the motions of smiling and her offspring Robert a lofty prefect with his new motor-cycle, Billy a rather grubby specimen of an over-bullied fag. Carol had been a placid blonde sausage...and Lilian Marston, who looked like Garbo and just wanted fun with men.

First Edition - 1948

Pan paperback - 1972

There are several 'dated' references (both David and Penny smoke, as do most of the other characters) and (authorial) opinions, which would not sound well at a women's-lib gathering: ...in a way put all the responsibility of future developments completely on his shoulders. But in a way, too, that was how he as a man wanted it to be. The delicate balance of human relationships, of a woman and a man with two separate and well-defined personalities learning to adjust them to each other, would have been overweighted if she had been more confident, more dominant than he was. And again, Penny's thoughts that the main trouble is that we try to be independent creatures, and we are not. We are dependent on others. And mostly, if we would only be honest enough to admit it, we are dependent on men. They give us the balance we need. She smiled as she imagined the professional feminist's retort to such an admission. It is also pretty clear that David's sister's friend, tall, large-boned, tweed-suited Florence Rawson is a prototype lesbian, although the word is never said; that Penny's employer, Bunny, whose hair waves and his voice curls, is not interested in women; and the throwaway comment about The Times reporting of the carefully worded trial, which deceives nobody, of the two Guardsmen in Hyde Park.

It would not be a MacInnes book without strongly-held view on Communism and Fascism. Not particularly necessary for the novel, but nor totally 'bolted on'. Her Chapter Twenty-one, 'Post-mortem on Friendship', is a strong attack by David on the communist Marain, thin and dark, with a gentle voice and savage phrases. David rejects the latter's views: I believe that there is to be a change they (the majority) have to earn it for themselves. Not by violence, but by thinking things out. Get an intelligent electorate, and then an intelligent election, and soon there will be plenty of house-cleaning. David a little later comments adversely on another man, Breen (worryingly a friend of his sister's): If it becomes fashionable among the so-called intelligentsia to wear black shirts, Breen will be out there in front of them mimicking Mussolini...he has a mountainous inferiority complex. He has to justify himself by extremes. He thinks strong methods prove strength. This is pure MacInnes territory!

It feels very much like a 'first book', which are nearly always autobiographical. The dialogue rings so true, the descriptions so apt, the constant worry of young minds about the other's true feelings so accurate, the mini misunderstandings and quarrels, the tensions in both families. On too many occasions, the commentary seems so heartfelt, so personal: Perhaps it is completely natural that women in love forget everything else. It is not selfishness, for their thoughts are not on themselves, but on those they love. It is an absorption, all the more complete as love increases, that shuts them away from any other emotional interests. It all ends well: David gets an excellent First, a job travelling in the United States and with Penny. Her parents have finally agreed with her grandfather and the two get married with a luncheon at the Savoy. And the honeymoon? - a week on the island of Inchnamurren, of course!

Born in Scotland in 1907, MacInnes was only four years older than David and Penny in 1932. She studied for a Librarianship Diploma at University College, London (Penny's Slade was in a section of the complex) and may well have lodged in Gower Street, if not at Penny's forbidding Baker House. She married Gilbert Highet in September 1932 (a month David and Penny had planned for!)

It is a book best read by those on the same emotional journey - in their late teens or early twenties - OR for the elderly looking back (as did Penny's grandfather), fondly reminiscing over faded photographs and smiling at the memories. I know, because I do.

No comments:

Post a Comment