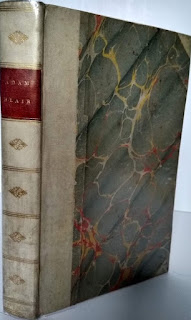

First edition - 1822

This is the first novel I have read of J. G. Lockhart's - I have 'dipped and skipped' through the seven volumes of his Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott. The idea for Adam Blair came from a true story, which Lockhart heard from his Church of Scotland minister father. The fictitious Manse of Cross-Meikle must have been a dour, then passionate, then again melancholic abode - truly a house of sorrow for most of the time. The reverence still sown for the seed of the martyrs (viz. Adam Blair and his antecedents) weighed heavily in the west of Scotland. It needed a Scott or Galt to lighten the puritanical gloom, not Charlotte's half-sickly mind. The Biblical admonition, 'Let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall', alas, comes too late to save Blair. A more modern rendition of the Fall would not have used 30 asterisks!

What do the critics say?

The London Magazine: knows not what real and pure interest can be excited, by this filthy betrayal of vice in characters and in situations to which we are accustomed to look for the decencies, the virtues, and the white enjoyments of life!

Secondary Scottish Novels (Edinburgh Review 1823) states that it is a story of great power and interest, though neither very pleasing, nor very moral, nor very intelligible...there are many things both absurd and revolting in its details...the story is clumsily put together, and the diction, though strong and copious, is frequently turgid and incorrect.

David Craig (Scottish Literature and the Scottish People 1680-1830, 1961), immediately makes a very telling point: it represents the conventional moral feelings of the age (certainly not the 21st century's!). Nothing is done to show a psychological link between their act and its aftermath; Lockhart is swept forward blinded by his assumptions about sin and conscience, for it is plain that he could not conceive (or dare to show) the 'sin' (which is not even clearly given) as anything but an enormity. Pertinent point. ...the customary moral simplicities (I will not say decencies) are observed, and Mr Blair must help his community by publicly atoning for his sin to the bitter end...Adam Blair does leave conventional morals undisturbed.

Francis Russell Hart (The Scottish Novel: A Critical Survey, 1978) argues that Scots is used to suggest a general character of traditional simplicities and pieties, and is saved for characters who have them. Strahan, the local lad of sharp parts who has become an Edinburgh lawyer, uses no Scottish idioms at all. Interestingly, Hart, suggests that Charlotte's sentimental self-indulgence (e.g. her letter to Blair) finds a subtle echo in his own, and the echo leads to Blair's sexual surrender. Her corrupt, worldly sympathy is carefully distinguished from the restrained and delicate compassion of his presbyterian parish. There is little dialogue...Lockhart seems to be opposing Galt's provincial community of traditional talkers to his own quiet, respectful concern...the peasant's hut to which Adam returns following his fall is a type of local ancestral shrine where he must seek purification. Charlotte's husband begins as a cultural characture and ends as a different agent of grace.

Thomas C. Richardson (Character and Craft in Lockhart's Adam Blair, 1979) suggests that it was important to stress the story was founded on truth for the English this documentation was necessary to lend credence to the severity of Blair's punishment, and for the Scots, to render credible the restoration Of Blair to his parish ministry...the novel illustrates truths about the human condition...a conflict of principle and passion...is a tragic tale of innocence and experience.

Unusually, I have quoted at length from the critics. The two contemporary extracts show how far we are removed from the mores of two hundred years ago - perhaps too far? It is hard to credit the scenes of such deep remorse evinced by the two main characters. It is not entirely clear how much their subsequent illnesses is caused by physical (dunking in the river) or psychological torments. Blair goes off to the life of a peasant - humble, silent, laborious, penitent, devout. However, one accepts it is a tale of its times and the subsequent recall to the ministry, admittedly after ten long years, does sweeten the pill somewhat. I feel most sorry for Blair's young daughter Sarah - a mere eight years-old on her mother's death, swept along in the passions she knew not what of, to end her days in the lowly familial cottage, in calmness, meriting and receiving every species of attention at the hands of her father's late parishioners.

To move from Galt's humour and Scott's delineation of character to what is, after all, a sombre tale lessens the 'enjoyment' of the reading. I found one or two of the purple passages - usually Lockhart's attempt to describe scenery - over the top. However, there are one or two quite well-drawn - if sketchily - characters, other than Adam and Charlotte: Mrs Semple, the Lady Dowager of Semplehaugh, Dr Muir, old John Maxwell, the church elder; but the ruffian Strahan is too much of a pasteboard.

Lockhart speaks to a contemporary reader, not to one of our century, when he writes, those who know what were the habitudes and feelings of the religious and virtuous peasantry of the west of Scotland half a century ago,,,(will understand the) deep and painful shock which was given to every simple bosom among them...Today, the story would certainly make the pages of our tabloids, but would not now be regarded as that unusual.

----------------------------------------

I have been re-reading (8th August) Francis Jeffrey's Secondary Scottish Novels (Edinburgh Review, October 1823) and he has this to say about Lockhart's novel:

It is a story of great power and interest, though neither very pleasing, nor very moral, nor very intelligible...there is no great merit in the design of this story, and there are many things both absurd and revolting in its details: but there is no ordinary power in the execution; and there is a spirit and richness in the writing...but the story is clumsily put together, and the diction, though strong and copious, is frequently turgid and incorrect. Clearly written by an 1823 Conservative!

No comments:

Post a Comment