Thursday, 30 September 2021

Matthias Barton Mysteries 3 and 4

Tuesday, 28 September 2021

Methodism

Writing yet again about the rather negative approach to Methodism and Methodists in the early 19th century Scottish novelists I have been reading, I thought I would make a few observations below.

On our weekend London trip recently, we visited the London Charterhouse. John Wesley attended there as a pupil between 1714 and 1720. There is a plaque to him on the wall of the passage leading to the chapel.

Sunday, 26 September 2021

Lockhart's 'The History of Matthew Wald' - 1824

Saturday, 25 September 2021

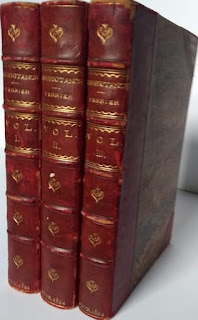

Susan Ferrier's 'The Inheritance' - 1824

Susan Ferrier's second novel was not published until six years after Marriage. Once again, it was anonymous. In April 1823, Susan's brother John visited John Murray to discuss producing The Inheritance. When William Blackwood heard of these early negotiations, however, he pleaded with Susan to give the work to him. His initial offer of £500 was refused, but, in September 1823, he paid her one thousand pounds sterling to be settled for by a bill at twelve months from the date of publication. The novel was published in the Spring of 1824 and it was an immediate success.

Friday, 24 September 2021

Matthias Barton Mysteries 1 and 2

When we visited south Somerset in mid-August, we had half a day in the lovely market town of Sherborne, just over the border in Dorset. My purpose was to photograph the small monastic gateway

Tuesday, 21 September 2021

Pius IX - The Pope who would be King

A weekend in London and a chance to browse in yet more bookshops. On my way to one of my favourites - Jarndyce, opposite the entrance to the British Museum, I stopped off at Judd Books. I was very pleasantly surprised; essentially it was a 'posh' remainder store, with a tremendous selection of History and Literature. I could have spent a fortune. I purchased just one volume and read it at the Caledonian Club and on the train back to Derby.

Thursday, 16 September 2021

An Edinburgh Pilgrimage II

Of course, another major reason for returning to Scotland's capital city is to scour its second-hand bookshops. Alas, like everywhere else - London, Bath, York, Brighton etc. - several have closed for good; victims, not just of the recent Covid scourge, but of the Internet and a new uncultured generation. There is no time for reading if your mobile phone is beckoning.

For all that, I did manage to visit three old favourites and they delivered some interesting tomes. First to Mcnaughtan's Bookshop and Gallery at 3a Haddington Place, where I chatted to Derek Walker, who I first met at the York Book Fair. It seemed the same as ever, apart from a slight retreat from two rooms. The Scottish section (a feature of all three bookshops) was interesting, but had no great 'finds'. I did purchase two volumes published by T. N. Foulis.

Tuesday, 14 September 2021

An Edinburgh Pilgrimage I

Thursday, 2 September 2021

Scott's 'Redgauntlet' 1824