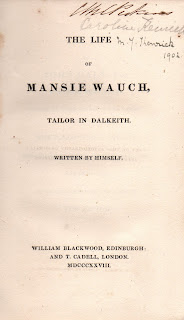

After a month's break, I return to my last dozen or so early Nineteenth Century Scottish novels.

I must admit I was slightly disappointed with Mansie Wauch. I had read that it was in John Galt's style (The Annals, The Provost), and there is a fulsome tribute to Galt in the dedication by his sincere friend and admirer. However, it didn't quite have the sharpness of humour (although there were examples of drollery) or the clean, knitting together of the storyline.

My main structural criticism is the insertion of an 80 page history-cum-romance on Gustavus Vasa of Sweden. Entitled The Curate of Suverdiso. A Tale of the Swedish Revolution, it has no bearing at all on the rest of the novel. Moir's excuse for telling it was that Mansie ended up with papers found by me in the side-pocket of the grand velvet coat, bought from the auld-farrant Welsh flunky with the peaked hat and the pigtail. Well okay, but put it at the end, almost as a separate tale. Essentially, it is the story set in the period known as the Swedish War of Liberation where the whereabouts and activities of Vasa are still the subject of guesswork as much as of fact. David Moir, quite skilfully it must be admitted, constructs a tale around the pursued Vasa in the province of Dalecarlia. The Curate of Suverdsio and his daughter Margaret give succour to Count Eric Voss (Vasa in disguise), who is then joined by Regner Beron (Margaret's sweetheart). All's well that ends well, with quite a good twist at the end. There are a couple of anti-Roman Catholic sentences - the Curate says time, custom, self-interest, have not been able to blind mine eyes to its crookedness - to its mummeries - to its monstrous absurdities...; the glorious doctrines of the immortal Luther sprung up conquering and to conquer the gloomy, debasing, and detestable superstition of the Roman Church - but, to be fair, it is in the context of the Reformation spreading to Sweden. In fact, sections of the tale become a mere History lesson. The author is also guilty of a besetting sin of so many of the early 19th century writers - descriptive purple passages.

Mansie's Shop Door

Many a time one is reminded of Galt's Provost Pawkie (deliberately so by the author), with his smugness and boasting (often unconsciously) and there is plenty of humour to be found as a result. Mansie, (born in 1765), thirty years an elder of Master Wiggie's kirk; an upstanding (if often frightened - too regularly in an terrible funk) member of the Volunteers (and one of his Majesty's confidential servants...); and proud owner of a housie (two rooms and a kitchen, not speaking of a coal-cellar, and a hen-house) and shop, with the sign of the Goose and Pair of Shears rampant, had good cause to be proud. The story of the Bailie and Deacon and others ignorantly trying to eat cigars (curious-looking long black things) offered by a newly arrived Nabob from the East Indies is very well told; as is the tale of Mansie's first and last play.

The first day I got my Regimentals on

Mansie redeems himself by his obvious love and care for his wife, Nanse Cromie (if ever a man loved, and loved like mad, it was me...), his son Benjie and the town of Dalkeith. He is an obvious patriot and anti Whigs, the Black-nebs, the Radicals, and the Friends of the People, together with the rest of the clanjamphrey.

There were enough Scotch words to make me reach for my trusty Scottish Dictionary, but I guessed at many of them so as not to slow down my reading speed. There are some wonderful words to savour: cockernony - the gathering of a woman's hair; scougged - hid; craps - stomachs; brans - calves; mouls - graves; snab - shoe-maker; spaining-bash - milk fever.

No comments:

Post a Comment