Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown

first edition - 1822

This three-decker was published anonymously, but the title pages gave clues as to the author, by listing his previous works: The Mystery, or Forty Years ago and Calthorpe, or Fallen Fortunes. Those in the know would have pointed to Thomas Gaspey (1788-1871) as the progenitor.

Gaspey was a Parliamentary reporter on the Morning Post, where he also contributed dramatic reviews and reports on treason trials. He stayed with the newspaper for sixteen years before becoming a sub-editor at the Courier, a government paper. In 1828 he bought a share in the Sunday Times, where he raised it as a literary and dramatic organ. He died, aged 83, at his home at Shooter's Hill. Two of his sons were also involved in literary works. Gaspey was again to write on Lord Cobham - who played a vital role in this novel - when he published The Life and Times of the Good Lord Cobham (1843)

The Preface is useful, as it gives the reader the authorial intention: The author, - the compiler, perhaps, he should rather call himself, has supplied from imagination what he considered necessary to give them [correct scenes] connexion; but generally he has kept as closely as possible to history. Gaspey then went on to reveal his sources - Maitland, Pennant, Malcolm, Douce, Henry, Beckmann, Baker, Monstrelet, Hollingshed, and Grose (I have only heard of three of them) - are responsible for most of the historical facts and local representations. The author also explains why he thinks there were printed works around as early as 1415.

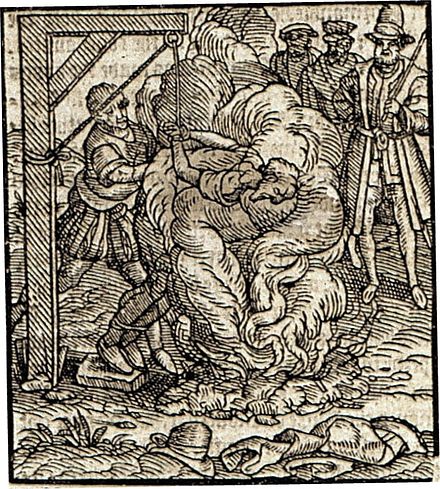

I am very partial to John Wycliffe and the Lollards for several reasons. One can trace a journey over the centuries to Methodism; Lutterworth is not far from Ashby de la Zouch and my semi-adopted area of England; and I admire his/their role is highlighting and castigating the malign influence of the Roman Catholic Church in medieval times. Gaspey sets the scene well - in fact, the first piece of dialogue does not occur until page 41 in Volume I. He gives us not only a compelling account/appraisal of Oldcastle (Lord Cobham) but also of the recently appointed (1414) Archbishop of Canterbury - Henry Chicheley (c.1364-1443). The latter, portrayed as a fierce opponent of Lollardy and intimately involved in the death by burning of Cobham on 14 December 1417, is also given a few scruples. At least the latter makes it to page 138 of the final volume.

Oldcastle being burnt for heresy

The story follows the fictitious sons of Oldcastle and Lord Charlton of Powys (1370-1421), who was responsible for capturing the former on his estates in Herefordshire and who was able to claim a hefty reward, much to the chagrin of his 'son'. Scenes are set in Prague and Constance, where Jan Hus is tried, condemned and burnt, much to the horror of Oldcastle's 'son' and 'daughter'. Once again, the reader gets the feeling that the story was 'stretched' rather to fit the requirements of the [in]famous three-decker, and there are various meanderings in both England and France, before true love for most of the characters ends happily. This includes King Henry V, who is again portrayed sensitively ( his shock at seeing Catherine of France's beauty is well described!) It was unusual to read of Agincourt, that the scene was set after the battle and vibrantly described the carnage and suffering - arms, legs and heads were scattered in every direction, in frightful confusion. One feels the regular descriptions of the London streets and buildings could, perhaps, have been cut.

So, Edward and Alice Oldcastle; Matilda and Sir Thomas Venables; Octavius, son of Lord Powys; Eugene De Marle, Madam D'Aumont and Baron de Chlume wend their fictitious way through the actualité of 1413 to 1417, occasionally helped by extremely unlikely coincidences, and quite skilfully guided by the author. At least William Whittington M.P., the elder brother of the famous Sir Richard ('Dick') was really who the author says he was!

There was one nice touch of black humour, which is worth repeating: ...Holywell, they took their way to the far-famed spring said to have been furnished by the intrepid virtue of St. Winifred, whose sanctified career, according to the legend, was not to be terminated even by the process of beheading, which in other cases has furnished a very efficient check to the finest enthusiasm.

No comments:

Post a Comment