- I found too often the musical score was pretentious

- the scenes set in the steel working town were beyond grim

- the bar culture was exactly what I don't like (despise!)

- the repulsive American cars of the time

- the Russian roulette scenes bordered on the gratuitous

- I find helicopters eerie and menacing

- I have never liked Meryl Streep - God, is she unpleasant to look at!

- I am not a fan of Christopher Walken (78 years-old this very day); another unprepossessing face

- I found none of the characters sympathetic

- I don't like deer hunting (or any shooting of animals)

- I don't like the aesthetics of the Russian Orthodox Church

- nearly every scene went on far too long - the wedding and reception, the car driving away from the fat guy on the road, the roulette scenes... It could have been cut by 60 minutes - easily.

Wednesday, 31 March 2021

50 Great War Films: The Deer Hunter

Sunday, 28 March 2021

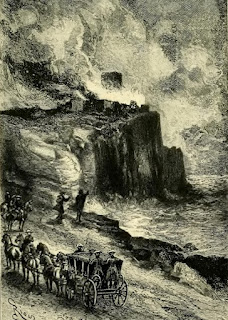

Scott's 'The Abbot' 1820

Thursday, 25 March 2021

Scott's 'The Monastery' 1820

Tuesday, 23 March 2021

Scott's 'Ivanhoe' 1820

Thursday, 18 March 2021

50 Great War Films: Cross of Iron

Monday, 15 March 2021

Mary Brunton's 'Emmeline' 1819

Sunday, 14 March 2021

50 Great War Films: A Bridge Too Far

Friday, 12 March 2021

Scott's 'A Legend of Montrose' 1819

Wednesday, 10 March 2021

50 Great War Films: Tora! Tora! Tora!

I am going to start with our friend Roger Ebert, who felt that the movie was one of the deadliest, dullest blockbusters ever made and that it suffered from not having some characters to identify with. He was equally scathing about The Battle of Britain. Well, I disagree and why should we have to identify with any of the characters? We weren't there - do we identify with actors/characters like John Wayne or Steve McQueen, anyway? Stupid criticism. Why can't we enjoy relatively factual historical events without having to feel part of them. I bet it was really because the film looked at the event from the Japanese point of view as well as the American and it showed Americans making mistakes. What I would agree with (as other critics highlighted) was that some of the 'action' scenes were clearly involving model ships and planes, and the same ship sinking/aircraft blowing up was seen from different angles later on. Yes, the plotline may have been slow, but it was trying to recreate the episodes leading up to that Sunday morning of 7th December 1949. And, yes, the need for all those captions - for personnel and places - felt excessive (and I still couldn't make out who-was-who half the time), but there were a lot of individuals involved. So, bah to Mr. Ebert.

The film had its world premiere on 23 September 1970 in New York, Tokyo, Honolulu and Los Angeles. It was the ninth highest grossing film of 1970 and was a major hit in Japan.

Tuesday, 9 March 2021

50 Great War Films: Patton

Monday, 8 March 2021

Scott's 'The Bride of Lammermoor' 1819