The Bride of Lammermuir - first edition 1819

When the last laird of Ravenswood to Ravenswood shall ride

And woo a dead maiden to be his bride,

He shall stable his steed in the Kelpie's flow,

And his name shall be lost for evermoe!

The legend is that The Bride of Lammermoor was written by an author in considerable pain. It was the product of a drugged and abnormal condition...yet there are no loose ends in the book. (John Buchan) However, the manuscript is written in Scott's normal hand, showing no trace of illness. It seems more likely that he had nearly completed it before he became ill. I purchased the four volume first edition on 5th October 1985, for only £10.

The main incidents of the tale are founded on real events taking place in the Scottish families of Lord Rutherford (the original of Ravenswood) and Lord Stair (the Lord Keeper Sir William Ashton - whose disposition was crafty and not cruel and who had spent his life in securing advantages to himself by artfully working upon the passions of others), such as the enmity between the families and the love of their descendants for each other. Lady Ashton is intimated by Scott to represent Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and her conduct in the story to be founded on that of Lady Stair. Her only interest was herself: she no more lost sight of her object than the falcon in his airy wheel turns his quick eyes from his destined quarry. She is Lady Macbeth to Ashton's vacillating Macbeth.

The character of Bucklaw, bears some resemblance to the Laird of Baldoon. I am Frank Hayston of Bucklaw, and no man injures me by word, deed, sign, or look, but he must render me an account of it.

Ailsie Gourlay is a prototype of that period in Scottish history. One could also surmise that Colonel Douglas Ashton was not unlike Shakespeare's Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet. In fact, there is much to link the story to Romeo and Juliet: Volume I Chapter IV and Volume II Chapter VI both start with extracts from the play. However, one could argue there are three witchlike figures (Macbeth) and elements of Richard III and Hamlet sneaking in!

The warnings of the two old, faithful servants of the Ravenswood family - Alice Gray and Caleb Balderstone - convince any reader that ill fortune awaits Edgar Ravenswood and Lucy Ashton.

Lucy Ashton and the Master of Ravenswood

at Mermaiden's Well

One is aware of a sense of marching fatality (Buchan). Lucy is gentle and mild, rather than weak or stupid, and possesses strong affections, unlike her tricky father or vindictive mother. Ravenswood is a tragic figure who dominates the story. Her gentle beauty attracts him and his dark intensity fascinates her. The scene when he returns (founded on the real event) and denounces the Ashtons is powerful; including the crossing of 'swords' with the Presbyterian clergyman, the Rev. Mr. Bide-the-Bent (a typical humorous Scott name) frae the Mosshead.

Craigengelt is a typical Scott character - a scheming parasite, whom we can despise. The Marquis of A--, in whom the fire of ambition had for some years replaced the vivacity of youth; a bold, proud, expression of countenance, yet chastened by habitual caution, is another well-drawn figure. Lady Ashton employing Lucky Ailsie Gourlay to frighten her daughter by stories and prophesies about the Ravenswood family is sheer evil. Gourlay and the other two village ancients - Annie Winnie and Maggie - remind one of the first scene in Macbeth; Scott's three earthly witches are really cunning, malevolent old crones, hated of all and hating and they function as a chorus.

What little humour there is comes from Caleb Balderston, whose attachment to the house of Ravenswood was the principal passion of his mind. His various schemes to hide the truth of his master's poverty are very amusing. He represents the past, freezing Edgar in his feudal role, inventing new falsehoods and excuses. Caleb provides both comedy and pathos. There are also the lovely cameos from Johnny Mortsheugh, the grave-digger and the cooper's family in Wolf's-hope.

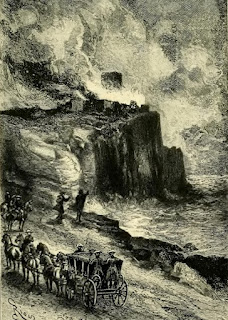

Caleb's 'fire' at Wolf's Crag

The first sight we have of Wolf's Crag is ominous: the tower itself, which, tall and narrow, and built of greyish stone, stood glimmering in the moonlight, like the sheeted spectre of some huge giant. A wilder, or more disconsolate dwelling, it was perhaps difficult to conceive. The sombrous and heavy sound of the billows, successively dashing against the rocky beach at a profound distance beneath, was to the ear what the landscape was to the eye - a symbol of unvaried and monotonous melancholy, not unmingled with horror. Gothic nightmares, here we come! The final chapter is Scott's own invention, with its telling of Ravenswood's and Balderstone's fates, and it piles on the tragic element.

Let Buchan have the last word: The book, Scott's single unrelieved tragedy, stands apart from the rest. It has none of his mellow philosophy or his confidence in the ultimate justice of things....for all its magnificence, it is outside the succession of the greatest tragedies, for it wounds without healing, and perturbs without consoling... in his sickness things came to Scott out of primordial deeps.

No comments:

Post a Comment